Nonprofit Ground Zero for the '67 Riots

How the "Party" headquarters-turned-speakeasy ignited a city

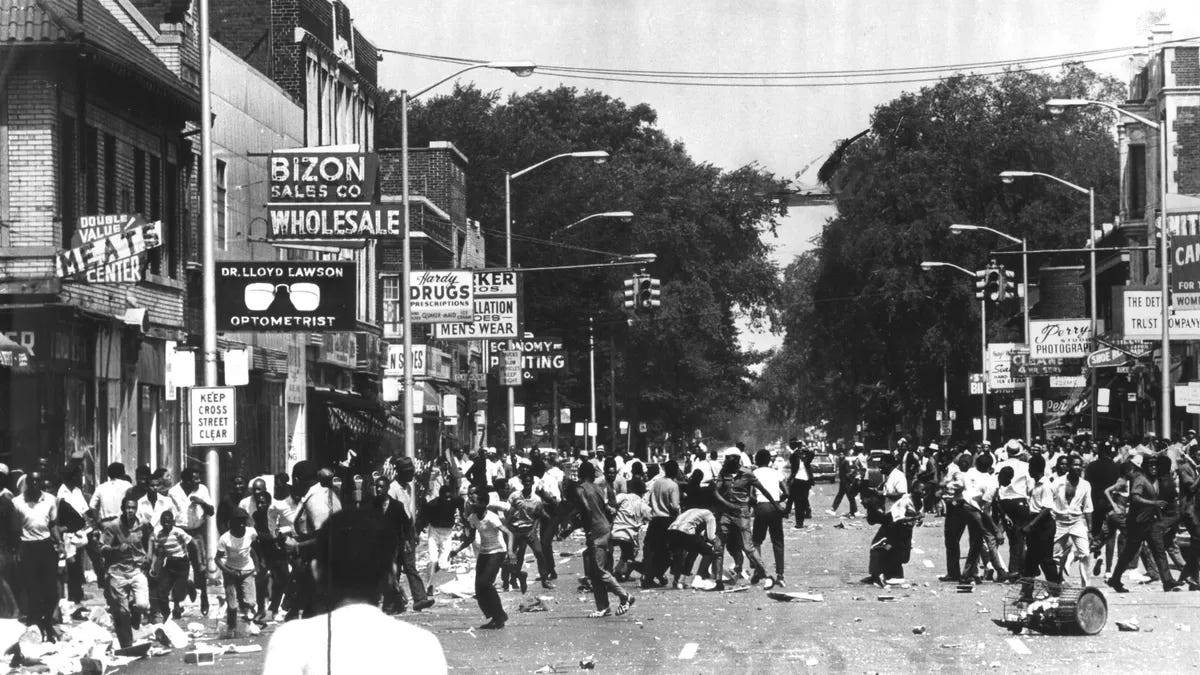

In the early morning hours of Sunday, July 23, 1967, a police raid at a nonprofit, political organization in Detroit’s 12th Street neighborhood touched off one of the most destructive riots in United States history.

By day, an office on the second floor of 9125 12th Street was the United Community League for Civic Action (UCLCA). At night, when the office door closed … a bar opened for business, the kitchen started taking orders, a juke box played Motown favorites; and the space turned into what locals colorfully called a “blind pig,” an unlicensed drinking establishment that offered a lot more than just a cold beer.

12th Street’s Reputation

Detroit Free Press reporter William Serrin, whose work helped earn the newspaper a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the riot, called 12th Street “one of the most volatile Negro streets in Detroit.”

The area had a population density twice the city average and its highest crime rate. According to author Kenneth Stahl, 12th Street was known as “Sin Strip, Avenue of Fun or Pocket Ghetto.”

Quoting a 12th Street regular, Stahl described the dichotomy: “There was a daytime 12th Street, and there was a nighttime 12th Street, and they didn’t overlap.”

In the weeks just prior to the riot, police had been focused on reducing prostitution on 12th Street. On July 1, a prostitute was killed, and area residents believed the police had shot her.

“Folks in the neighborhood call it simply ‘the Democratic Club.’”

Location, Location, Location

The defunct Economy Printing building served as UCLCA’s headquarters. In its follow-up reporting on the riot, the Detroit Free Press stated, “Folks in the neighborhood call it simply ‘the Democratic Club.’”

As director of the United Community League for Civic Action, William Scott II presided over both the second floor’s day and night activities.

Stahl claims “Economy Printing was considered an ideal location in the heart of a burgeoning black populace. Scott had been told ‘to hold onto this good location when political activity was slow, even if it meant running a speakeasy.”

Who was giving Scott orders to hold onto the location remains an open question.

Police Raid

At 3:00 a.m., on the morning of July 23, 1967, Scott wasn’t playing politics, he was a businessman working late, hosting a crowd of more than eighty revelers celebrating the safe return of two Vietnam veterans.

The Detroit Free Press described Scott’s thinking about the raid: “It was unconstitutional, the fuzz crashing his little get-together.”

The Black community viewed raids on the blind pigs as racially motivated. Since Prohibition, these speakeasys had dotted the urban landscape, providing entertainment for a population unwelcome at many Detroit restaurants and bars.

In some cases, it was members of the Black clergy urging the police to shut down the blind pigs because they brought crime and misery to families and the neighborhood.

Scott’s political activities

Serrin reported, “Scott thinks of himself more as politician than party-giver.”

Chartered in 1964, the United Community League for Civic Action had grown and was building a grassroots organization to back local candidates running for office, get out the vote, and secure a seat at the table for the neighborhood, a seat it had long been denied.

A mimeographed broadside found at the UCLCA office in the aftermath of the riot set out the organization’s goals.

· “To use our headquarters as … referral centers for … persons seeking … ADC [Aid to Dependent Children] and welfare assistance.

· To fight for … increased job upgrading.

· To fight for housing for disadvantaged people.”

Scott had success in his efforts. He told the Detroit Free Press he had sent 13 precinct delegates to the Democratic State Convention in 1966. He also bragged about his organization’s growing influence saying politicians making the rounds, looking for Black support had spent time at “The Democratic Club.”

Stahl reports, “Politicians often helped pay the expenses of the United Community League because Scott could get the word out.”

At least for some, UCLCA had a radical reputation. In a 1987 article entitled “Why Black Power is important,” Detroit’s Black-owned newspaper, the Michigan Chronicle reported the following statement: “Joseph Williams, the President of the West Grand Blvd-Clairmont Improvement Association, said he had heard of Molotov cocktails being stockpiled by the United Community League for Civic Action.”

3:45 a.m., Sunday, July 23, 1967

On that fateful Sunday morning, two Black, plainclothes police officers gained entrance to the 2nd floor UCLCA headquarters-turned-blind pig. They were expecting the usual crowd, maybe 20 or so people. Instead, they found more than 80 people.

Thinking many of the guests would have outstanding warrants, Detroit Police Department officials made the decision to arrest everyone at the location. As police coordinated transportation and began hauling people out of the building and into paddy wagons, a crowd began to form and watched as their neighbors were being arrested. Someone threw a bottle.

Over the next five days, the city of Detroit erupted – looting, arson, sniping. The Michigan State Police, Wayne County Sheriff’s Department, and the Michigan Army National Guard were called in. Tanks patrolled the streets. It took until Thursday, July 27, to get the city under control.

The count from those five days in July: 43 dead; 1,189 injured; over 7,200 arrests; and more than 400 buildings destroyed.

In his 1970 memoir, Hurt, Baby, Hurt, William Walter Scott III, claimed responsibility for throwing the first bottle at a police officer and starting the riot.

###

Readers should not conclude the United Community League for Civic Action was solely responsible for the 1967 Detroit Riot or that the organization had anything other than a random role in events of 1967. It was, however, a nonprofit with a political mission engaging in criminal activity, and it happened to be at the center of a tragic moment in U.S. history.